“…give me liberty or give me death!” – Patrick Henry, March 23, 1775

Today is 235th anniversary of Patrick Henry’s famous “give me liberty or give me death” speech presented to the First Continental Congress. To commemorate it, I am posting this excerpt from my book proposal, Words Mattered: The 200 Quotations That Created, Shaped, and Explain American History.

Soon after the Boston Massacre, King George III of Britain wrote to his prime minister, Lord North, “I am very fond of the measures you are taking with the end of bringing the Americans to their duty. I do not however, want to drive them to despair, only to submission.” But the British resolve reflected in the king’s words was met with an equal measure of colonial resistance, in the form of a movement galvanized by Sam Adams and the Sons of Liberty.

In December 1773 Adams grasped an opportunity to put his organizational talents to work by leading a protest against the British tax on tea. He assembled 150 Sons of Liberty dressed as Mohawk Indians and led their charge onto tea-carrying British ships docked in Boston Harbor. Methodically and without violence, the protesters hurled over three hundred chests of tea into the water, destroying cargo worth almost $100,000 at the time.

In December 1773 Adams grasped an opportunity to put his organizational talents to work by leading a protest against the British tax on tea. He assembled 150 Sons of Liberty dressed as Mohawk Indians and led their charge onto tea-carrying British ships docked in Boston Harbor. Methodically and without violence, the protesters hurled over three hundred chests of tea into the water, destroying cargo worth almost $100,000 at the time.

The gesture had a catalytic effect on the evolving revolutionary passion. To colonists who maintained allegiance to the British, known as Tories or loyalists, the Boston Tea Party was a shameful display of vandalism. To the British it was an alarmingly blatant example of defiance of royal authority. Their reaction was severe. With the support of the king, Parliament passed a series of measures against the American colonists. In Great Britain they were called the Coercive Acts; in the colonies they were usually referred to as the Intolerable Acts.

The Intolerable Acts were aimed directly at the hotbed of subversive activity—Massachusetts. The new orders closed the port of Boston, curtailed Massachusetts colonial government, made appointment of local officials the power of the royal governor, restricted town meetings, and extended the Quartering Act, paving the way for a permanent presence of British troops in Boston.

These harsh actions by the British provided the radicals with what Sam Adams called “the perfect crisis,” leading to the formation of the First Continental Congress in Philadelphia in September 1774. The Congress laid the foundation for colonial unity and for organized rebellion.

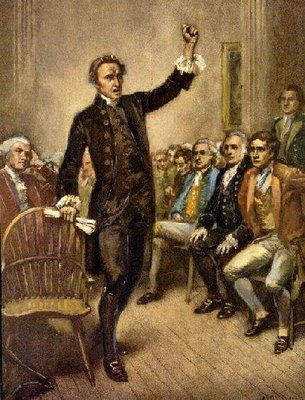

Among the fifty-six delegates meeting in Philadelphia was prominent Virginia lawyer Patrick Henry. The thirty-six-year-old Henry had a reputation as a sharp mind and a firebrand, a skilled orator who expressed zealous support for the patriots’ cause. Addressing his Continental Congress colleagues, Henry implored:

Among the fifty-six delegates meeting in Philadelphia was prominent Virginia lawyer Patrick Henry. The thirty-six-year-old Henry had a reputation as a sharp mind and a firebrand, a skilled orator who expressed zealous support for the patriots’ cause. Addressing his Continental Congress colleagues, Henry implored:

The next gale that sweeps from the north will bring to our ears the clash of resounding arms! . . . Why stand we here idle? . . . Is life so dear, or peace so sweet, as to be purchased at the price of chains and slavery? . . . I know not what course others may take; but as for me, give me liberty or give me death!

Henry’s rhetoric helped inspire the First Continental Congress. Speaking in one voice for the first time, the delegates vowed to support the resistance in Massachusetts and to arm themselves in case of British attack. To British ears Henry’s words and the actions of the Congress represented betrayal—the foolish behavior of an impulsive child.

More British soldiers were sent to Boston, as were three top generals. King George III joined Parliament in speaking the bellicose language of war, promising the “rabble in Boston” that “force will be met with force.” British major John Pitcairn echoed the king’s sentiments when he explained just days before the Revolutionary War began, “I am satisfied that . . . burning two or three of their towns will set everything to rights.”