“Ich bin ein Berliner.” – John Kennedy, June 26, 1963

It is the most famous American quotation ever spoken in a foreign language. Forty-seven years ago today–fewer than five months before his death–President John Kennedy stood before Brandenburg Gate in West Berlin, within close view of the ominous extension of the Berlin Wall, and expressed in German an iconic statement of the Cold War that remains among American history’s most profound affirmations of human rights: “Ich bin ein Berliner (I am a Berliner.)”

It is the most famous American quotation ever spoken in a foreign language. Forty-seven years ago today–fewer than five months before his death–President John Kennedy stood before Brandenburg Gate in West Berlin, within close view of the ominous extension of the Berlin Wall, and expressed in German an iconic statement of the Cold War that remains among American history’s most profound affirmations of human rights: “Ich bin ein Berliner (I am a Berliner.)”

Kennedy came to Germany at the end of an incredibly consequential, almost two decade period that saw the nation transform from Nazi tyranny to an emerging and prosperous democracy threatened by communism. Following World War II, Germany was divided into zones, which were administered by the wartime allies Great Britain, the Soviet Union, and the United States, as well as France. Construction of what became the Berlin Wall began without warning in August 1961. The communists in Germany and their Soviet sponsors explained that it was necessary to halt aggressive capitalist influence and stop western spies from entering the area and undermining local authority.

However, the overwhelming motivation for the creation of the Wall was the communist desire to stem the steady and increasing flow of Germans seeking greater political and economic freedom out of the Soviet zone into the West. This situation was particularly problematic in the East because a disproportionate number of the over two million people migrating to the West were skilled workers and highly educated individuals. This “brain drain” depleted the already weakened eastern Germany further and infuriated its leaders because so many of those leaving had been trained and educated at the expense of the communist regime.

However, the overwhelming motivation for the creation of the Wall was the communist desire to stem the steady and increasing flow of Germans seeking greater political and economic freedom out of the Soviet zone into the West. This situation was particularly problematic in the East because a disproportionate number of the over two million people migrating to the West were skilled workers and highly educated individuals. This “brain drain” depleted the already weakened eastern Germany further and infuriated its leaders because so many of those leaving had been trained and educated at the expense of the communist regime.

Although Kennedy immediately and publicly opposed the construction of the Berlin Wall, he was not in a position to do much to counter it. He had been weakened by the Bay of Pigs fiasco and he recognized the potentially catastrophic consequences of confronting the Soviets militarily over the Wall. There is evidence that privately he viewed it as a clear indication that the Soviet premier Nikita Krushchev hoped to avoid war with the United States. According to President Kennedy’s close friend and aide Kenneth P. O’Donnell, Kennedy reacted to news of the Wall’s creation by saying, “Why would Khrushchev put up a wall if he really intended to seize Berlin? There wouldn’t be a need of a wall if he occupied the whole city. This is his way out of his predicament. It’s not a very nice solution, but a wall is a hell of a lot better than a war…This is the end of the Berlin crisis…We’re going to do nothing now because there is no alternative except war. It’s all over, they’re not going to overrun Berlin.”

Kennedy’s arrival in Germany began a ten-day European trip that would later include visits to Ireland, Great Britain, Italy, and Vatican City. Though there were many destinations on the itinerary, this first stop was clearly the most important. In the less than two years since the construction of the Berlin Wall, that city had been the central point in the Cold War struggle between the the United States and the Soviet Union and Kennedy knew that his speech would be watched and studied carefully on each side of the ideological divide.

Historian Richard Reeves, in his 1993 book President Kennedy: Profile of Power, noted that Kennedy shared the beginning of his planned speech in West Berlin with the American military commander in the city, General James Polk:

“Fifteen years ago this very day…,” it began, recounting the beginning of the Berlin Airlift. “Ten years ago this month a spontaneous uprising of the freedom-loving people of the Eastern Zone was repressed…two years ago a shameful wall was built. The story of West Berlin is many stories…I will carry away from this city an inspiring picture of all I have seen.”

“This is terrible, Mr. President,” said the general. “I think so, too,” Kennedy said.

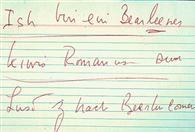

Later in the day, Kennedy traveled in his motorcade, standing in an open air vehicle as it moved slowly through the crowded streets. He decided to scrap his platitudinous speech and replace it with something sharper, jotting down the phonetic pronunciation of the phrase that would later come to define it on an index card (pictured, left.) Following a brief tour of the area west of the Berlin Wall, Kennedy approached the microphone to address the vast expanse of American-flag-waving Germans–later estimated to number over two million–who had gathered to hear and cheer him. Viewable from his place was the Brandenburg Gate, which had giant red banners draped on it by communist authorities in East Berlin to deny its inhabitants a view of the American president and the huge crowd assembled to welcome him. Though he spoke only about five hundred words, Kennedy was successful in, as Reeves describes, “rallying the ecstatic crowd in to a great roaring animal, like the city’s symbol, a standing bear.”

Later in the day, Kennedy traveled in his motorcade, standing in an open air vehicle as it moved slowly through the crowded streets. He decided to scrap his platitudinous speech and replace it with something sharper, jotting down the phonetic pronunciation of the phrase that would later come to define it on an index card (pictured, left.) Following a brief tour of the area west of the Berlin Wall, Kennedy approached the microphone to address the vast expanse of American-flag-waving Germans–later estimated to number over two million–who had gathered to hear and cheer him. Viewable from his place was the Brandenburg Gate, which had giant red banners draped on it by communist authorities in East Berlin to deny its inhabitants a view of the American president and the huge crowd assembled to welcome him. Though he spoke only about five hundred words, Kennedy was successful in, as Reeves describes, “rallying the ecstatic crowd in to a great roaring animal, like the city’s symbol, a standing bear.”

After beginning with pleasant greetings for his German hosts, Kennedy assailed the communist system by challenging those who support it to confront the oppression represented by the Wall with his repeated hammering of the words, “Let them come to Berlin.”

There are many people in the world who really don’t understand, or say they don’t, what is the great issue between the free world and the Communist world. Let them come to Berlin.

There are some who say that communism is the wave of the future. Let them come to Berlin.

And there are some who say in Europe and elsewhere we can work with the Communists. Let them come to Berlin.

And there are even a few who say that it is true that communism is an evil system, but it permits us to make economic progress. Lass’ sie nach Berlin kommen. Let them come to Berlin!

Kennedy then proceeded to powerfully and eloquently mock the communist claim that the Wall was somehow an instrument designed to protect liberty, and in doing so, he made the case that helped emphasize how the Wall was a propaganda disaster for the Soviets:

Freedom has many difficulties and democracy is not perfect, but we have never had to put a wall up to keep our people in, to prevent them from leaving us…. While the wall is the most obvious and vivid demonstration of the failures of the Communist system, for all the world to see, we take no satisfaction in it, for it is…an offense not only against history but an offense against humanity, separating families, dividing husbands and wives and brothers and sisters, and dividing a people who wish to be joined together.

Focusing on his message of solidarity with the besieged West Germans, and by extension with all those suffering under communist tyranny, Kennedy concluded:

Freedom is indivisible, and when one man is enslaved, all are not free. When all are free, then we can look forward to that day when this city will be joined as one and this country and this great continent of Europe in a peaceful and hopeful globe. When that day finally comes, as it will, the people of West Berlin can take sober satisfaction in the fact that they were in the front lines for almost two decades.

All free men, wherever they may live, are citizens of Berlin, and, therefore, as a free man, I take pride in the words “Ich bin ein Berliner.”

The crowd was euphoric. Kennedy was enormously pleased with the speech, but there quickly emerged pangs of concern that it could undo his administration’s delicate and highly desired efforts to reach accord on a nuclear test ban treaty with the Soviets, because Kennedy had in essence just explained that there was no working with the communists. Kennedy sought to round the edge of his words later that evening, explaining, “I do believe in the necessity of great powers working together to preserve the human race.” Negotiations proceeded and on July 25, the United States and the Soviet Union reached agreement on a treaty that banned nuclear testing in the atmosphere, space, and underwater. Within two months, the pact was approved by the Senate and signed into law by Kennedy.

The crowd was euphoric. Kennedy was enormously pleased with the speech, but there quickly emerged pangs of concern that it could undo his administration’s delicate and highly desired efforts to reach accord on a nuclear test ban treaty with the Soviets, because Kennedy had in essence just explained that there was no working with the communists. Kennedy sought to round the edge of his words later that evening, explaining, “I do believe in the necessity of great powers working together to preserve the human race.” Negotiations proceeded and on July 25, the United States and the Soviet Union reached agreement on a treaty that banned nuclear testing in the atmosphere, space, and underwater. Within two months, the pact was approved by the Senate and signed into law by Kennedy.

Hours after the speech was over and the throngs of people had left the Rudolph Wilde Platz (Plaza)–now named the John F. Kennedy Platz–Kennedy was aboard Air Force One on his way west to his family’s ancestral homeland of Ireland. He turned to his chief speechwriter Ted Sorensen and said, “We’ll never have a day like this one, as long as we live.”